I recently put some new tires on one of my bikes and got my first opportunity to try out the very nice traditional-looking Compass brand tires -- specifically, the 28mm Chinook Pass. The Compass tires are billed as having exceptionally supple casings which should yield a great ride and handling with very low rolling resistance. Over the years, Jan Heine's Bicycle Quarterly magazine has published the results of a number of real-world-based tests to measure tire rolling resistance, and those tests helped lead to the development of the Compass tires. In the interest of disclosure, Bicycle Quarterly and Compass Cycles are the same company, and Heine is very up-front and forthcoming about that fact - but I'm inclined to put good faith in their test results which have helped lead a welcome trend in the bicycle industry toward larger volume tires.

Most of the Compass tires are available with either a black or natural tan sidewall. I always opt for the natural tan for my vintage-styled bikes. People with more modern rides might choose the black sidewalls if that suits their style better. All the different tires use the same traditional file pattern tread, and are available with one of two casing options: Standard, and Extralight. The Extralight is a little thinner and is supposed to be even more supple than the Standard casing, but it adds nearly $20 to the price. I opted for the Standard casing Chinook Pass for $57 -- not inexpensive, but that does appear to be the going rate for high-quality, high-performance clincher tires these days. Panaracer Pasellas sell for less, but they have a noticeably thicker casing and tread. I would not consider them a high-performance tire (that's not a criticism - it's just a matter of different tires for different missions).

The previous tires I had used on my Mercian King of Mercia were the Challenge Paris-Roubaix tires. I have to be honest in saying that, from a performance standpoint, those are tough to beat. The Paris-Roubaix is billed by Challenge as an "open-tubular" -- not just a "clincher" tire. That is, they use the same exact casing as their tubular tires, but instead of sewing the casing around the tube, they use the wire bead of a clincher. Okay - that's just a matter of semantics, or marketing-speak. But the tires were wonderful - springy, fast, and comfortable. The only criticism I've seen against them is that some feel they are a bit too vulnerable to flats. However, I rode mine for several years and wore the tread down completely and only suffered one flat in that whole time. The price on the Paris-Roubaix seems to have gone up since I last bought them. I'm certain I didn't pay more than about $55 each ($60 at the very most), but checking around lately, the going rate seems to be about $75 each. Gulp!

Hoping for a similar riding experience, I got the Compass Chinook Pass when the Paris-Roubaix finally wore out. I got the new tires mounted with no difficulty. I was able to pull the bead over the edge of the rim all the way 'round with no tools. A little pulling here and pinching there, and I was able to get them mounted perfectly straight and even as well. They seem very well made - a quality product.

I've gotten out for several rides on the new tires. They do live up to the advertising in that they do feel fast, and comfortable. Handling around corners is good, and on chip-seal paving (really common on rural backroads in my area) they do a good job of keeping the "buzz" to a minimum.

It's way too early to tell about long-term durability, but I don't expect any problems. I've had excellent experiences with Panaracer-made Rivendell tires like the Roly Poly and the Jack Browns, as well as Panaracer Pasellas. I will be interested to see how the lighter, more supple casing affects the durability on the Compass tires. Certainly, as I get more miles on these, if I observe anything that would change my long-term impressions, I'll post something. I should note, however, that the tires specifically do not have any kind of extra puncture resistant measures in their construction. Adding extra puncture resistant layers and belts can cut down on flats, obviously, but such layers also make for a stiffer casing and add rolling resistance. Though Heine mentions in his articles that they use the Compass tires over all kinds of roads without issues, I might suggest that if someone is really concerned about punctures on their heavy-duty commuting bike that they ride over roads strewn with broken glass or goat-head thorns, they are probably not in the market for a lightweight performance tire. Just getting that out there.

So far, though, I'd say that if riders are interested in a light, fast, performance tire - especially one that looks right on a classic-styled bike - then the tires from Compass give us several more options and in a nice variety of available sizes.

Wednesday, August 31, 2016

Monday, August 29, 2016

New Old Bottom Bracket Standard

In a move that shouldn't really come as much of a surprise, several bike companies are releasing new mountain bikes this year with a new and improved bottom bracket system that promises to solve once-and-for-all the problems of ill-fitting, creaking, press-fit bottom brackets.

So, what exactly is this new solution? The real irony is that the latest "new" bottom bracket standard isn't new at all. Several mountain bike makers are bringing back the traditional threaded bottom bracket.

The new-for-'17 Specialized Enduro has plenty of state-of-the-art mountain bike technology, and a variety of updates and changes - lots of them with catchy proprietary names: SWAT Door Integration, ManFu Link, and X-Wing layout (don't even ask me what any of that means). But look closely at the listed specs, past all the hot new tech, and you'll see something that was dismissed as obsolete just a couple of years ago. The new Enduro comes with a 73mm threaded bottom bracket, just like any decent mountain bike made since the '90s and through the first decade of the '00s.

They aren't the only ones, either. Niner bikes has put a 73mm threaded bottom bracket into its newest Jet 9 RDO, a short-travel trail bike.

It looks like some of the bike makers are considering the traditional threaded BB because of its well-known reliability, even under harsh conditions. Some also cite the ability to use threaded bottom bracket shell inserts that also incorporate threaded bosses for some common chain guides.

Some companies never actually abandoned the threaded bottom bracket - like Santa Cruz. But now, instead of having to explain why they stuck with the "old tech" when everyone else was switching to "new-so-they-must-be-better" press-fit bottom brackets, Santa Cruz can now sit back and say "See, we were right all along."

Does this mean threaded bottom brackets are coming back for all bikes? Probably not - or at least, not yet. Citing weight, some companies are still saying they don't want to add the extra gram or two that comes with bonding a threaded aluminum insert into their stupid-light carbon fiber frames. Because people will absolutely be able to feel the extra grams - just like they immediately notice the weight loss when they spill a mouthful of water from their water bottle. More likely, it comes down to the same old argument that manufacturers try to downplay for their buyers - that when doing everything possible to slash manufacturing costs, eliminating the need for a precisely machined and threaded bottom bracket shell in a popped-out-of-a-mold carbon frame represents a savings they'd rather not give up. That's one of the main reasons for going to press-fit in the first place.

Are threaded bottom brackets poised for a real comeback? It's too soon to say for sure - but it's an interesting development all the same.

So, what exactly is this new solution? The real irony is that the latest "new" bottom bracket standard isn't new at all. Several mountain bike makers are bringing back the traditional threaded bottom bracket.

|

| New for '17 Specialized Enduro. Threaded bottom brackets, anyone? |

They aren't the only ones, either. Niner bikes has put a 73mm threaded bottom bracket into its newest Jet 9 RDO, a short-travel trail bike.

It looks like some of the bike makers are considering the traditional threaded BB because of its well-known reliability, even under harsh conditions. Some also cite the ability to use threaded bottom bracket shell inserts that also incorporate threaded bosses for some common chain guides.

Some companies never actually abandoned the threaded bottom bracket - like Santa Cruz. But now, instead of having to explain why they stuck with the "old tech" when everyone else was switching to "new-so-they-must-be-better" press-fit bottom brackets, Santa Cruz can now sit back and say "See, we were right all along."

|

| Santa Cruz - Still with a threaded bottom bracket. "We knew you'd be back." |

Are threaded bottom brackets poised for a real comeback? It's too soon to say for sure - but it's an interesting development all the same.

Friday, August 26, 2016

An Unusual SunTour Derailleur

A couple of days ago I got a question from a reader, Phil S., about this derailleur he found in a box of old inventory he got from a closed bike shop. Pictures of the derailleur were also floated around some of the bike forums and email groups hoping for some identification. It's left a lot of people wondering "what the heck is this thing?"

Such a puzzle. . .

Looking closely, you can see that the unit is marked "Taiwan" which gives a clue. Suntour was bought out and merged with SR and moved to Taiwan in the early '90s. Could this thing possibly have been made as recently as the 1990s? It sure doesn't look like it, but that's a pretty compelling piece of information.

From the way the derailleur is oriented, it really appeared to me that it was meant to be mounted below the chainstay, ahead of the rear dropout. In that way, it would have a very straight cable path (one can see a cable stop mounted on the far right side) and would move in a roughly horizontal path in front of the rear axle.

That kind of "backwards" orientation would not be unheard of for Suntour, which used a similar mounting location and orientation for its S-1 derailleur in the early '90s. As far as I know, that derailleur was standard equipment on only one bike, the 1993 Schwinn Criss Cross:

Using these derailleurs as a guide, I suspected that the derailleur was almost certainly meant for folding bikes, or perhaps some other bike where this under-the-chainstay mounting location would offer some protection.

Such a puzzle. . .

Looking closely, you can see that the unit is marked "Taiwan" which gives a clue. Suntour was bought out and merged with SR and moved to Taiwan in the early '90s. Could this thing possibly have been made as recently as the 1990s? It sure doesn't look like it, but that's a pretty compelling piece of information.

From the way the derailleur is oriented, it really appeared to me that it was meant to be mounted below the chainstay, ahead of the rear dropout. In that way, it would have a very straight cable path (one can see a cable stop mounted on the far right side) and would move in a roughly horizontal path in front of the rear axle.

That kind of "backwards" orientation would not be unheard of for Suntour, which used a similar mounting location and orientation for its S-1 derailleur in the early '90s. As far as I know, that derailleur was standard equipment on only one bike, the 1993 Schwinn Criss Cross:

|

| The S-1 was almost like an updated Nivex derailleur, which was a really sweet shifting unit from the late 1930s, and the grandfather of parallelogram derailleur designs. As I understand it, one of the benefits of this arrangement for Suntour was that it made the derailleur slightly less vulnerable to damage in the event of a fall or other accident because it didn't project outward as much as one mounted on the rear dropout. |

|

| Another "backwards" facing derailleur, made by SR/Suntour, is the Dahon Neos, made for folding bikes. Again, the advantage is that it is slightly less vulnerable when the bike is folded up. |

Yet another clue comes from a fairly rare derailleur known as the Hole Shot:

I forwarded the photos of the mystery derailleur over to Michael Sweatman in the U.K., whose extensive derailleur collection is featured on the Disraeli Gears website. Though it isn't currently shown on the site, it turns out Sweatman has a nearly identical derailleur to Phil's mystery unit.

Sweatman confirmed for me my suspicion that the mystery derailleur was meant to be mounted below the chainstay, not unlike the S-1. He seemed to agree that the unit may have been meant for some folding bikes (probably really cheap, utilitarian ones). He also suggested it could have been for children's bikes. That makes a good deal of sense, and seems to match up to the 2-speed Hole Shot for BMX bikes.

Putting it all together, I think what we have here is the coelacanth of bicycle components: An anachronistic-looking no-frills stamped steel 2-speed derailleur; probably made either for children's bikes or utilitarian home-market folding bikes (or perhaps both); mounted under the chainstay ahead of the rear dropout; and made in the early '90s by Suntour shortly after being moved to Taiwan.

So, is the mystery solved? Well, not entirely. We still don't have a model name for it. And we can only make some educated guesses about its intended use. To me, though, the biggest unanswered question is why Suntour would still have been making something like this in the modern era - when it seems like such a step backwards?

|

| The SunTour Hole Shot derailleur was a 2-speed unit made for BMX bikes in the early '80s. It mounted on the rear dropout, but hung down below and forward of the rear axle. There's no parallelogram here, just a sliding rod to move the cage from one cog to the other. |

Sweatman confirmed for me my suspicion that the mystery derailleur was meant to be mounted below the chainstay, not unlike the S-1. He seemed to agree that the unit may have been meant for some folding bikes (probably really cheap, utilitarian ones). He also suggested it could have been for children's bikes. That makes a good deal of sense, and seems to match up to the 2-speed Hole Shot for BMX bikes.

Putting it all together, I think what we have here is the coelacanth of bicycle components: An anachronistic-looking no-frills stamped steel 2-speed derailleur; probably made either for children's bikes or utilitarian home-market folding bikes (or perhaps both); mounted under the chainstay ahead of the rear dropout; and made in the early '90s by Suntour shortly after being moved to Taiwan.

So, is the mystery solved? Well, not entirely. We still don't have a model name for it. And we can only make some educated guesses about its intended use. To me, though, the biggest unanswered question is why Suntour would still have been making something like this in the modern era - when it seems like such a step backwards?

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

Super Bike? Or Super Hype?

There hasn't been a blog update for a few days - sorry about that. I'm trying to get used to a new schedule at work, and there hasn't been a lot of writing time.

Anyhow. . .

With the 2016 Olympics having just wrapped up, I found this article the other day on the CyclingTips website about the Project '96 Superbike, built for the '96 Olympic Games in Atlanta.

Some readers may remember the GT Superbikes, though it was 20 years ago so there's no guarantee. Twenty years ago?! Wow. It's hard to believe.

The Superbike II, as it was known, was the culmination of a major engineering effort between USA Cycling, GT Bicycles, and Mavic components, with input from people such as aerodynamics expert Chester Kyle, and the aerodynamics lab at General Motors. The bike was recognizable for its unusual top-tube-less carbon fiber monocoque frame, airfoil shapes, and extremely narrow aerodynamic profile. When viewed from the front, the bike was barely any wider than its disc wheels. The bike also had no seat stays, and the seat mast was shaped to act as a large fairing for the rear wheel.

By the way - Superbike II? Well, there was a GT Superbike I, which was made of aerodynamic profiled aluminum tubing, and has been described as sort of a "stopgap" on the way to the design freedom that carbon fiber would give the designers for the "ultimate" racing bike, Superbike II.

The CyclingTips article reveals quite a bit about Project '96 Superbike, hailing it as a revolution -- perhaps even the apex of the no-holds-barred aerodynamic school of bicycle design. I also detect a note of "just think of where we'd be today" lamentation in the story -- if only the UCI weren't so backwards. "The bike was fast. Perhaps too fast," the article says. It goes on:

"Unfortunately for GT and other similarly innovation-minded companies, though, the UCI set out to squelch those technological advantages shortly after the Superbike II broke ground in Atlanta . . . Superbike just pushed it too far."

Just think where racing bikes would be today - if only. . .

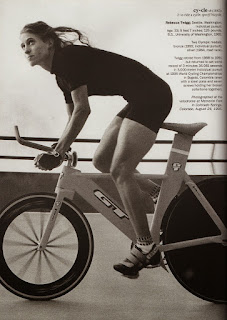

Hmmm. . . I wouldn't be a retrogrouch if I could agree with that. But then it's also barely mentioned that despite the huge investment in the design and the technology (the bikes were said to have cost $15,000 each in 1996) the U.S. results in Atlanta were truly lacklustre with only two silver medals -- Erin Hartwell in the 1 kilo time trial, and Marty Nothstein in the sprint. Rebecca Twigg was probably the greatest American hope on the U.S. cycling team, and she was eliminated after her second heat. She blamed her disappointing performance at least in part on the Superbike. Twig apparently didn't like the fit and wanted to use the bike she was more familiar with. She later said that arguments with coach Chris Carmichael over the issue took away her focus.

Regarding fit, it's pretty apparent just from looking at the bike that dialing in the perfect fit for an individual racer wasn't exactly an easy thing to do. The integrated seat mast meant that making any adjustments to saddle height or angle was a complicated and slow process.

And even if one accepts the notion that the carbon fiber monocoque design was a great thing, I'm not sure I can accept that the Superbike was all that unique for the time. It certainly wasn't the "secret weapon" that some hypesters would have us believe.

For example - look at the Lotus 108. Originally designed in the mid 1980s, the bike was shelved when the UCI ruled such designs illegal for competition in 1987. In 1990, the ban on monocoque designs was lifted, and the 108 was used for a number of international races, including the '92 Olympics in Barcelona, ridden to gold under Chris Boardman.

Then there was the Pinarello Espada. In 1994, Miguel Indurain rode the Espada to a new Hour Record. He used a road-going version of the same basic design in the time trial stages of the '95 Tour de France.

In the same '96 Olympics that saw the U.S. team use the Superbike, Pinarello had another unusual monocoque design: the Parigina.

Anyhow. . .

With the 2016 Olympics having just wrapped up, I found this article the other day on the CyclingTips website about the Project '96 Superbike, built for the '96 Olympic Games in Atlanta.

Some readers may remember the GT Superbikes, though it was 20 years ago so there's no guarantee. Twenty years ago?! Wow. It's hard to believe.

The Superbike II, as it was known, was the culmination of a major engineering effort between USA Cycling, GT Bicycles, and Mavic components, with input from people such as aerodynamics expert Chester Kyle, and the aerodynamics lab at General Motors. The bike was recognizable for its unusual top-tube-less carbon fiber monocoque frame, airfoil shapes, and extremely narrow aerodynamic profile. When viewed from the front, the bike was barely any wider than its disc wheels. The bike also had no seat stays, and the seat mast was shaped to act as a large fairing for the rear wheel.

By the way - Superbike II? Well, there was a GT Superbike I, which was made of aerodynamic profiled aluminum tubing, and has been described as sort of a "stopgap" on the way to the design freedom that carbon fiber would give the designers for the "ultimate" racing bike, Superbike II.

The CyclingTips article reveals quite a bit about Project '96 Superbike, hailing it as a revolution -- perhaps even the apex of the no-holds-barred aerodynamic school of bicycle design. I also detect a note of "just think of where we'd be today" lamentation in the story -- if only the UCI weren't so backwards. "The bike was fast. Perhaps too fast," the article says. It goes on:

"Unfortunately for GT and other similarly innovation-minded companies, though, the UCI set out to squelch those technological advantages shortly after the Superbike II broke ground in Atlanta . . . Superbike just pushed it too far."

Just think where racing bikes would be today - if only. . .

|

| Rebecca Twigg, aboard Superbike I. Twigg was probably the best hope for US Cycling in the '96 Olympics, but it was not to be. Regarding Superbike II, Twigg was not a fan. |

Regarding fit, it's pretty apparent just from looking at the bike that dialing in the perfect fit for an individual racer wasn't exactly an easy thing to do. The integrated seat mast meant that making any adjustments to saddle height or angle was a complicated and slow process.

And even if one accepts the notion that the carbon fiber monocoque design was a great thing, I'm not sure I can accept that the Superbike was all that unique for the time. It certainly wasn't the "secret weapon" that some hypesters would have us believe.

For example - look at the Lotus 108. Originally designed in the mid 1980s, the bike was shelved when the UCI ruled such designs illegal for competition in 1987. In 1990, the ban on monocoque designs was lifted, and the 108 was used for a number of international races, including the '92 Olympics in Barcelona, ridden to gold under Chris Boardman.

|

| Lotus 108 |

|

| Indurain setting a new Hour Record in '94 on the Espada. |

|

| The same basic design as a road time trial bike helped take him to his 5th Tour de France victory. |

With what amounted to an "arms race" in designers trying to buy their way to more victories and gold medals, the UCI did change the rules again in 2000 to put limits on these increasingly outlandish bike designs, and with that, bikes like the Superbike II were done. The CyclingTips article seems to imply that the Superbike was the reason for the rules change, or at least the "straw that broke the camel's back," but as we can see, there were plenty of other bikes at the time that followed a similar plan, and if one looks mainly at race results as the measure, then the others had more to show.

Thursday, August 18, 2016

Bikes in Cinema - Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

"Meet the future."

With those words, Butch Cassidy (Paul Newman) takes Etta Place (Katharine Ross) for a ride on his new bicycle in one of the most memorable scenes from the classic film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

Made in 1969, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid bucks many of the typical conventions of Hollywood Westerns. For one thing, it is in many ways as much of a "Buddy Flick" as it is a Western. It's humorous without really being a comedy. And it features an anachronistic contemporary pop soundtrack -- most notably the Burt Bacharach song "Raindrops Keep Fallin' On My Head" sung by B.J. Thomas, which plays through the whole bicycle sequence in the film.

Far from being just a trite musical break from the film's plot about two of history's most famous outlaws, however, the bicycle scene is actually a pretty fantastic visual metaphor about the old ways of the Wild West giving way to the modern age. In fact, three times in the film, the bicycle is referred to as "the future," and what a fitting symbol of the future it was!

To get some context, it can be helpful to know a bit about the real Butch and Sundance, and the time in which they lived.

To get some context, it can be helpful to know a bit about the real Butch and Sundance, and the time in which they lived.

Butch Cassidy was born Robert Leroy Parker in 1866 to a poor Mormon family in Utah. Possibly to avoid bringing shame to his family, he changed his name. He was called "Butch," likely because he spent some time working in a butcher's shop, and took "Cassidy" after an early acquaintance named Mike Cassidy, who had a reputation for stealing cattle. The Sundance Kid's real name was Harry Longabaugh. Born in 1867 in Pennsylvania, he got his nickname after he was arrested in his teens for stealing a horse in Sundance, Wyoming. As part of an outlaw band known as the Wild Bunch, they had a long-running crime spree of bank and train robberies in the 1880s and '90s.

Where the plot of the famous film begins, it is actually near the end of the Wild Bunch days, in the late 1890s, just on the cusp of the 20th century. At this point in the story, after years of successful robberies, and tremendous fame that came through countless newspaper reports and sensationalist pulp publications, more dogged law enforcement strategies were starting to close in on Butch, Sundance, and the Wild Bunch, forcing them to go separate ways.

In the true-life version of the events, the railroads for many years had little recourse to stopping train robberies, apart from loosely organized posses raised by local sheriffs after-the-fact to try to find the culprits who could easily disappear into the "Hole in the Wall" or somewhere else along the outlaw trail. But by the end of the 1890s, the railroad companies contracted with independent police and investigation companies - the most famous of which was the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.

The Pinkerton's outfitted special train cars with horses and highly-trained and dedicated agents, ready to be dispatched quickly in the event of a train robbery. Although the Pinkerton's aren't mentioned directly, a scene in the film portrays just such a train being dispatched after a robbery where the Wild Bunch blows a train car to splinters with dynamite. Agents in the film version then pursue Butch and Sundance relentlessly for several days and nights, with the outlaw pair continually looking over their shoulders asking, "Who ARE those guys?"

The technique that really helped lead to the end of the Wild Bunch, though, was the practice of recording and tracking the serial numbers on the stolen money. Tracking those serial numbers and following the money trail helped lead the Pinkertons to several members of the gang. In the real-life story, bills from the dynamited rail car (yes, that actually happened) led detectives to a couple members of the Wild Bunch. Some were killed. Others went to prison.

Another element of a more modern world that led to the gang's downfall was this famous photograph:

In a lot of ways, it was clear that the Old West, or the Wild West, was disappearing - being displaced by a more "Mild" West, spanned by telegraph lines, and attracting "softer," more respectable people moving from the East. The Pinkerton's symbol was an unblinking eye, with the slogan "We Never Sleep." Under that watchful eye, the modern world with its new 20th century law enforcement techniques meant that the kind of crime spree that the real Butch and Sundance enjoyed for so long was quickly coming to an end. With members of their gang dead or captured, and the Old West they knew so well rapidly disappearing, Butch and Sundance left for South America, taking Sundance's girl Etta Place with them.

In the film, this is where the symbolism of the bicycle comes full circle. As the trio prepare to leave for good, Butch ditches the bicycle, saying "The future's all yours, you lousy bicycle." The bicycle -- symbol of the future and the new century -- is rejected as the outlaws head for a place that still resembles the Wild West of the past.

Is it necessary to give a Spoiler Alert warning when talking about a movie that's nearly 50 years old? If so, consider yourself warned.

In the movie, Butch, Sundance, and Etta go to Bolivia where they enjoy a new crime spree, robbing banks and gaining notoriety as "Los Bandidos Yanquis." In reality, the trio first went to Argentina and apparently attempted to live a reputable life as cattle ranchers until the Pinkerton detectives tracked them down, prompting them to cross over to Bolivia and renew their bank robbing ways.

Somewhere between Argentina and Bolivia, Etta Place left the pair and disappeared forever. Nobody knows what happened to her, or even if that was her real name (it likely wasn't). There are a few theories or legends about her identity and eventual whereabouts - at least one of which has her returning to the U.S. and living well into the 1950s, but there's nothing provable and it's all just speculation.

Likewise, there are some questions about the last days of Butch and Sundance. The conventional story, which is played up in the movie, is that they were tracked down by Bolivian authorities in 1908, surrounded, and killed in a blaze of gunfire. The real-life story is not quite as Hollywood-glorious as the movie version. though. It's true that the real Butch and Sundance were involved in a deadly gunfight with Bolivian authorities, but they are believed by historians to have died by self-inflicted gunshot wounds when their desire for escape proved hopeless. Then again, the two Yanquis who were killed in Bolivia were never positively identified, and only assumed to be the famous American outlaws. That uncertainty, along with the nostalgia and Romanticism of the Wild West, led many to speculate that the American bank robbers killed in Bolivia were not actually Butch and Sundance - and that the famous duo returned to the U.S. and lived out their lives under new identities.

A bit of trivia about the film:

The Wild Bunch in the movie is called the "Hole in the Wall" gang. The reason the group's name was changed was that another Western film was in production at about the same time as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. That film was Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch. So the name of Butch and Sundance's gang was changed to avoid confusion. "Hole in the Wall" was the name of one of their favorite hideouts.

The role of the Sundance Kid was originally meant to go to Steve McQueen, but disagreements about who would get top billing led to McQueen passing on it. Robert Redford was nowhere near as famous, having mainly been a T.V. actor (he once appeared in an episode of The Twilight Zone). Redford had no problem taking second billing to Newman - but the film would launch him overnight to Newman's superstar status.

Robert Redford opted to do some of his own stunts in the film, including a famous one where he runs along the top of the cars of a moving train, jumping across the gap from one car to the next. Paul Newman was angry at him for doing it because he didn't want to lose his co-star.

Paul Newman also did some stunts for the film. The trick riding in the famous bike scene was supposed to be done by a stunt-double, but Newman turned out to be a better bike rider.

With those words, Butch Cassidy (Paul Newman) takes Etta Place (Katharine Ross) for a ride on his new bicycle in one of the most memorable scenes from the classic film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

|

| "Raindrops keep fallin' on my head. . ." |

Far from being just a trite musical break from the film's plot about two of history's most famous outlaws, however, the bicycle scene is actually a pretty fantastic visual metaphor about the old ways of the Wild West giving way to the modern age. In fact, three times in the film, the bicycle is referred to as "the future," and what a fitting symbol of the future it was!

To get some context, it can be helpful to know a bit about the real Butch and Sundance, and the time in which they lived.

To get some context, it can be helpful to know a bit about the real Butch and Sundance, and the time in which they lived.Butch Cassidy was born Robert Leroy Parker in 1866 to a poor Mormon family in Utah. Possibly to avoid bringing shame to his family, he changed his name. He was called "Butch," likely because he spent some time working in a butcher's shop, and took "Cassidy" after an early acquaintance named Mike Cassidy, who had a reputation for stealing cattle. The Sundance Kid's real name was Harry Longabaugh. Born in 1867 in Pennsylvania, he got his nickname after he was arrested in his teens for stealing a horse in Sundance, Wyoming. As part of an outlaw band known as the Wild Bunch, they had a long-running crime spree of bank and train robberies in the 1880s and '90s.

Where the plot of the famous film begins, it is actually near the end of the Wild Bunch days, in the late 1890s, just on the cusp of the 20th century. At this point in the story, after years of successful robberies, and tremendous fame that came through countless newspaper reports and sensationalist pulp publications, more dogged law enforcement strategies were starting to close in on Butch, Sundance, and the Wild Bunch, forcing them to go separate ways.

In the true-life version of the events, the railroads for many years had little recourse to stopping train robberies, apart from loosely organized posses raised by local sheriffs after-the-fact to try to find the culprits who could easily disappear into the "Hole in the Wall" or somewhere else along the outlaw trail. But by the end of the 1890s, the railroad companies contracted with independent police and investigation companies - the most famous of which was the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.

The Pinkerton's outfitted special train cars with horses and highly-trained and dedicated agents, ready to be dispatched quickly in the event of a train robbery. Although the Pinkerton's aren't mentioned directly, a scene in the film portrays just such a train being dispatched after a robbery where the Wild Bunch blows a train car to splinters with dynamite. Agents in the film version then pursue Butch and Sundance relentlessly for several days and nights, with the outlaw pair continually looking over their shoulders asking, "Who ARE those guys?"

The technique that really helped lead to the end of the Wild Bunch, though, was the practice of recording and tracking the serial numbers on the stolen money. Tracking those serial numbers and following the money trail helped lead the Pinkertons to several members of the gang. In the real-life story, bills from the dynamited rail car (yes, that actually happened) led detectives to a couple members of the Wild Bunch. Some were killed. Others went to prison.

Another element of a more modern world that led to the gang's downfall was this famous photograph:

In a lot of ways, it was clear that the Old West, or the Wild West, was disappearing - being displaced by a more "Mild" West, spanned by telegraph lines, and attracting "softer," more respectable people moving from the East. The Pinkerton's symbol was an unblinking eye, with the slogan "We Never Sleep." Under that watchful eye, the modern world with its new 20th century law enforcement techniques meant that the kind of crime spree that the real Butch and Sundance enjoyed for so long was quickly coming to an end. With members of their gang dead or captured, and the Old West they knew so well rapidly disappearing, Butch and Sundance left for South America, taking Sundance's girl Etta Place with them.

In the film, this is where the symbolism of the bicycle comes full circle. As the trio prepare to leave for good, Butch ditches the bicycle, saying "The future's all yours, you lousy bicycle." The bicycle -- symbol of the future and the new century -- is rejected as the outlaws head for a place that still resembles the Wild West of the past.

Is it necessary to give a Spoiler Alert warning when talking about a movie that's nearly 50 years old? If so, consider yourself warned.

|

| Sundance and Etta Place, photographed in New York in 1901 where they stopped for a visit before boarding a steamship bound for Argentina. |

Somewhere between Argentina and Bolivia, Etta Place left the pair and disappeared forever. Nobody knows what happened to her, or even if that was her real name (it likely wasn't). There are a few theories or legends about her identity and eventual whereabouts - at least one of which has her returning to the U.S. and living well into the 1950s, but there's nothing provable and it's all just speculation.

Likewise, there are some questions about the last days of Butch and Sundance. The conventional story, which is played up in the movie, is that they were tracked down by Bolivian authorities in 1908, surrounded, and killed in a blaze of gunfire. The real-life story is not quite as Hollywood-glorious as the movie version. though. It's true that the real Butch and Sundance were involved in a deadly gunfight with Bolivian authorities, but they are believed by historians to have died by self-inflicted gunshot wounds when their desire for escape proved hopeless. Then again, the two Yanquis who were killed in Bolivia were never positively identified, and only assumed to be the famous American outlaws. That uncertainty, along with the nostalgia and Romanticism of the Wild West, led many to speculate that the American bank robbers killed in Bolivia were not actually Butch and Sundance - and that the famous duo returned to the U.S. and lived out their lives under new identities.

A bit of trivia about the film:

The Wild Bunch in the movie is called the "Hole in the Wall" gang. The reason the group's name was changed was that another Western film was in production at about the same time as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. That film was Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch. So the name of Butch and Sundance's gang was changed to avoid confusion. "Hole in the Wall" was the name of one of their favorite hideouts.

The role of the Sundance Kid was originally meant to go to Steve McQueen, but disagreements about who would get top billing led to McQueen passing on it. Robert Redford was nowhere near as famous, having mainly been a T.V. actor (he once appeared in an episode of The Twilight Zone). Redford had no problem taking second billing to Newman - but the film would launch him overnight to Newman's superstar status.

Robert Redford opted to do some of his own stunts in the film, including a famous one where he runs along the top of the cars of a moving train, jumping across the gap from one car to the next. Paul Newman was angry at him for doing it because he didn't want to lose his co-star.

Paul Newman also did some stunts for the film. The trick riding in the famous bike scene was supposed to be done by a stunt-double, but Newman turned out to be a better bike rider.

Friday, August 12, 2016

Kickstand Cyclery - Reopened

If you haven't visited the Kickstand Cyclery lately, there's been a lot to catch up with. The webcomic took a hiatus of several years starting in 2013, but for the better part of a year now, Yehuda Moon & the Kickstand Cyclery has been running regular updates, with new strips posted nearly every weekday.

Earlier this year, the comic's creators Rick Smith and Brian Griggs put up a Kickstarter effort to fund a Vol. 6 of the Kickstand Comics collection, along with a re-release of Vol. 5 which was a difficult book to find. Volumes 1-6 are now available for purchase on the website, either individually for those who just need to complete a collection, or bundled together in a whole set which can save some money. Or people can just read the entire series on the website (I like having the books, though).

A lot has happened at the fictional bike shop since the strip returned. One story line that Smith and Griggs brought back is the one involving Fred, the former owner of the Kickstand Cyclery, who was killed by a hit-and-run driver. Readers familiar with the strip probably know that Fred has been a ghost from the strip's beginning, visible only to Yehuda and Joe. That's a little detail that wasn't necessarily obvious from the start, but was revealed through clues over time. Recent strips reveal a breakthrough in the case that had gone cold for several years - but I won't reveal the big surprise. It's definitely worth following.

|

| A re-released Vol. 5, and the new Vol. 6 - now available. |

A lot has happened at the fictional bike shop since the strip returned. One story line that Smith and Griggs brought back is the one involving Fred, the former owner of the Kickstand Cyclery, who was killed by a hit-and-run driver. Readers familiar with the strip probably know that Fred has been a ghost from the strip's beginning, visible only to Yehuda and Joe. That's a little detail that wasn't necessarily obvious from the start, but was revealed through clues over time. Recent strips reveal a breakthrough in the case that had gone cold for several years - but I won't reveal the big surprise. It's definitely worth following.

|

| A breakthrough that re-opens a cold case. |

Though maybe not exactly a "breakthrough" of the same sort, something else that happened while the Kickstand Cyclery was temporarily "closed" was the introduction of fat bikes. As always, Yehuda and Joe have a wry observation:

And while there are some bike-culture debates that may never get settled, you can always count on a funny and unique take on the debate at the Kickstand:

The great thing about the Kickstand Cyclery, and Joe, Yehuda, Thistle, and the other characters who spend their days there, is that people all over the country could almost swear the shop is based on a bike shop they know. The characters reflect people that any obsessed cyclist can relate to, and the conversations and debates are ones we all hear and engage in. Depending on how you look at it, the Kickstand is not based on any real bike shop, and at the same time, it's based on many of the real bike shops that we all frequent.

It's nice to see it running again - and if you haven't paid the shop a visit lately, get on over there. You'll be glad you did.

Thursday, August 11, 2016

Olympic Cycling News

The midwest is currently trapped in some kind of tropic-like heat and humidity bubble right now, making any kind of outdoor activity a miserable nightmare. About the best thing right now is to stay where it's cool and watch the Olympics.

In cycling, the American men haven't done much of anything newsworthy, but the races have had their share of drama. Belgian Greg van Avermaet won the Men's Road Race after a crash on a fairly difficult descent took out several riders, including Vincenzo Nibali, who had been in a good position for victory. Chris Froome was hoping to get the Gold just weeks after winning his 3rd Tour de France, but it was not to be. He missed an important breakaway and finished 12th. Brent Bookwalter was the best placed American in the road race at 16th. Approximately 79 riders, including Taylor Phinney, did not finish the race - most due to crashes.

In the Women's Road Race, the same stretch of road that saw race-ending crashes in the Men's race was the site of a horrific crash with Dutch rider Annemiek van Vlueten. She had been in the lead on the descent of the Vista Chinesa, with under 11 kilometers to go, when the slick conditions took her down hard. Reports say she was unconscious for a long time afterwards, suffered a concussion, and had several spinal fractures. The sight of her lying motionless, crumpled on the side of the road was pretty disturbing. Thankfully, she is doing better and has posted updates on her condition.

Just behind van Vlueten on the road was American Mara Abbott who was suddenly in excellent position for Gold. However, exhausted and possibly a bit spooked by what had just happened to van Vleuten, Abbott was not able to hold off the group behind her. Abbott was passed with just 200 meters to go. In that group was van Vleuten's teammate Anna van der Breggan, who accepted the Gold with tears for her injured teammate. Emma Johansson of Sweden got the Silver, with Elisa Longo Borghini taking Bronze. Abbott had to settle for 4th.

Fabian Cancellara, AKA Spartacus, won the Gold in the Men's Time Trial - a fitting end to his career as he is set to retire. Tom Dumoulin of the Netherlands took the Silver, and Chris Froome had to settle for Bronze. American riders Taylor Phinney and Brent Bookwalter were 22nd and 23rd respectively.

Again, just as in the road race, the American women gave us more to cheer about here in the States. Kristin Armstrong (and no, she is NOT any relation to Lance) proved her dominance in the time trial by taking her 3rd consecutive Gold Medal in the event at the age of 42. (She turned 43 the next day!). At some point along the course, Armstrong developed a nosebleed, but continued to push herself to the maximum. She lost some time in the second split of the course to Russian cyclist Olga Zabelinskaya, who just finished an 18-month ban from the sport for doping - so victory for Armstrong was a matter of honor. The American poured on the speed at the end to claim the win. The finish scene was pretty great to watch as Armstrong, her nose still bleeding, collapsed from the effort - then her son was lifted over the barricades so they could have an embrace.

I think my favorite story, however, wasn't about the winners, but the person who took LAST in the Men's Time Trial, Dan Craven from Namibia.

Looking a bit like Yehuda Moon with his full beard, Craven wasn't even supposed to compete in the time trial. But because there were so many riders unable to compete due to injuries sustained in the road race, the self-deprecating Namibian team member (who had also crashed out of the road race) was a last-minute substitution. He didn't even have a proper time trial bike. Apparently his first reaction upon being asked to race was to say no - concerned that it would be too embarrassing. But after a moment to think about it, and getting some advice from friends, he relented.

Looking a bit like Yehuda Moon with his full beard, Craven wasn't even supposed to compete in the time trial. But because there were so many riders unable to compete due to injuries sustained in the road race, the self-deprecating Namibian team member (who had also crashed out of the road race) was a last-minute substitution. He didn't even have a proper time trial bike. Apparently his first reaction upon being asked to race was to say no - concerned that it would be too embarrassing. But after a moment to think about it, and getting some advice from friends, he relented.

Craven was the first to leave the start house, and was caught along the course by one of the riders who left after him, but when he crossed the finish line, he was in 2nd place - at least for a moment or two.

What's great about Craven is that he came in last, yet it doesn't even matter. He was truly proud just to be able to compete. After the race, he told reporters, "Look at me. I'm talking to (you), standing here, wearing 'Namibia' across my chest. I'm such a proud Namibian. I love my country. The chance to do this. I can say I competed in an Olympic time trial."

Yep - that's probably my favorite story so far.

In cycling, the American men haven't done much of anything newsworthy, but the races have had their share of drama. Belgian Greg van Avermaet won the Men's Road Race after a crash on a fairly difficult descent took out several riders, including Vincenzo Nibali, who had been in a good position for victory. Chris Froome was hoping to get the Gold just weeks after winning his 3rd Tour de France, but it was not to be. He missed an important breakaway and finished 12th. Brent Bookwalter was the best placed American in the road race at 16th. Approximately 79 riders, including Taylor Phinney, did not finish the race - most due to crashes.

In the Women's Road Race, the same stretch of road that saw race-ending crashes in the Men's race was the site of a horrific crash with Dutch rider Annemiek van Vlueten. She had been in the lead on the descent of the Vista Chinesa, with under 11 kilometers to go, when the slick conditions took her down hard. Reports say she was unconscious for a long time afterwards, suffered a concussion, and had several spinal fractures. The sight of her lying motionless, crumpled on the side of the road was pretty disturbing. Thankfully, she is doing better and has posted updates on her condition.

Just behind van Vlueten on the road was American Mara Abbott who was suddenly in excellent position for Gold. However, exhausted and possibly a bit spooked by what had just happened to van Vleuten, Abbott was not able to hold off the group behind her. Abbott was passed with just 200 meters to go. In that group was van Vleuten's teammate Anna van der Breggan, who accepted the Gold with tears for her injured teammate. Emma Johansson of Sweden got the Silver, with Elisa Longo Borghini taking Bronze. Abbott had to settle for 4th.

Fabian Cancellara, AKA Spartacus, won the Gold in the Men's Time Trial - a fitting end to his career as he is set to retire. Tom Dumoulin of the Netherlands took the Silver, and Chris Froome had to settle for Bronze. American riders Taylor Phinney and Brent Bookwalter were 22nd and 23rd respectively.

Again, just as in the road race, the American women gave us more to cheer about here in the States. Kristin Armstrong (and no, she is NOT any relation to Lance) proved her dominance in the time trial by taking her 3rd consecutive Gold Medal in the event at the age of 42. (She turned 43 the next day!). At some point along the course, Armstrong developed a nosebleed, but continued to push herself to the maximum. She lost some time in the second split of the course to Russian cyclist Olga Zabelinskaya, who just finished an 18-month ban from the sport for doping - so victory for Armstrong was a matter of honor. The American poured on the speed at the end to claim the win. The finish scene was pretty great to watch as Armstrong, her nose still bleeding, collapsed from the effort - then her son was lifted over the barricades so they could have an embrace.

I think my favorite story, however, wasn't about the winners, but the person who took LAST in the Men's Time Trial, Dan Craven from Namibia.

Looking a bit like Yehuda Moon with his full beard, Craven wasn't even supposed to compete in the time trial. But because there were so many riders unable to compete due to injuries sustained in the road race, the self-deprecating Namibian team member (who had also crashed out of the road race) was a last-minute substitution. He didn't even have a proper time trial bike. Apparently his first reaction upon being asked to race was to say no - concerned that it would be too embarrassing. But after a moment to think about it, and getting some advice from friends, he relented.

Looking a bit like Yehuda Moon with his full beard, Craven wasn't even supposed to compete in the time trial. But because there were so many riders unable to compete due to injuries sustained in the road race, the self-deprecating Namibian team member (who had also crashed out of the road race) was a last-minute substitution. He didn't even have a proper time trial bike. Apparently his first reaction upon being asked to race was to say no - concerned that it would be too embarrassing. But after a moment to think about it, and getting some advice from friends, he relented.Craven was the first to leave the start house, and was caught along the course by one of the riders who left after him, but when he crossed the finish line, he was in 2nd place - at least for a moment or two.

|

| Craven at the finish, sitting in 2nd place. Briefly. |

Yep - that's probably my favorite story so far.

Wednesday, August 10, 2016

Bike Safety 101: Bicycles Are Beautiful

There hasn't been an entry in the Bike Safety 101 series for many months now, but today's entry is a neat little blast from the past, Bicycles Are Beautiful from 1974, featuring one of the best-known celebrities of the day, Bill Cosby.

There hasn't been an entry in the Bike Safety 101 series for many months now, but today's entry is a neat little blast from the past, Bicycles Are Beautiful from 1974, featuring one of the best-known celebrities of the day, Bill Cosby.Current (and very sad, disturbing) revelations notwithstanding, in the 1970s Bill Cosby was a man on top of the world. After years of standup comedy and numerous top-selling comedy albums, his groundbreaking role on the television series I Spy (Cosby was the first African-American to have a starring role in a network TV series), followed by his first sitcom, The Bill Cosby Show ('69 - '70 - also a first, as the first African-American to have his own eponymous show), a 2-year stint on the Children's Television Workshop series The Electric Company, then his animated show Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids, Cosby was probably one of the most recognizable people in America, and beloved by people of all ages.

|

| Cosby presents the film from the workbench of a bike shop. His manner is quite a bit more subdued than the Cosby seen in countless Jello Pudding commercials spanning three decades. |

Bicycles Are Beautiful was well-timed for the American bike boom, which reached its peak in 1974, and saw record numbers of adults hitting the streets on two wheels. However, while the film does recognize and validate adult cycling, it still primarily focuses on children in much the same way most other bike safety films have throughout the decades. Social messages aside, it's likely that the first thing viewers will notice is Cosby's unusual way of pronouncing "Bicycle" -- it sounds very much like "bi-SIGH-cle."

|

| "And you don't have to stand in any lines to fuel up a bike. 'Cause the only fuel your bike burns is what your body provides. So you're not polluting the air, either. |

|

| Perhaps anticipating the short attention span of the kids who were the likely target of the film, there is a brief interlude with "Some Really Interesting Stuff About Bicycles & Bicycling." |

Then it's back to the safety test:

|

| Another part of the "safety test" involves identifying possible hazards on this young man's bike ride. |

I imagine that most Retrogrouch Blog readers should easily be able to score 90 - 100% on the test. (If you watch the film, track your score and leave a comment). Yes, I got 100.

After a final (and very dry) message from the head of the National Safety Council, it's back to Bill in the bike shop, ready to go for a ride on one of those fancy 10-speeds with "caliper brakes and Italian derailleurs."

|

| "It's time for a safe little spin around the block. . . Maybe we'll meet down the road somewhere, on a bike of course. And just remember, bicycles are beautiful." |

Overall, Bicycles Are Beautiful has an upbeat, groovy message about bicycling that reflects the two-wheeled reawakening of the time. Compared to some of the stern or even scolding bike safety films of the '50s and '60s that I've discussed here, this film was a step forward in that it at least acknowledged the viability of bicycles for commuting and transport, and not just as toys for kids. Though hailed by some writers for debunking certain misconceptions about where cyclists should ride, or their very rights to the road, my take on the film is that it is certainly more progressive than earlier examples, but its factual information is mostly par for the course. Nevertheless, in watching Bicycles Are Beautiful, one can't help but feel a fun sense of nostalgia.

I've tried for some time now to locate a good clean copy of Bicycles Are Beautiful, but the only one I've been able to find anywhere is a relatively mediocre transfer (with distracting counter digits imposed in the foreground) in two parts on YouTube.

Here's part one:

And part two:

Enjoy!

And if that's not quite enough groovy '70s Cosby nostalgia for you, take about half-a-minute to check out the opening theme from the original Bill Cosby Show - probably the most funk-tastic TV theme song of all time. Hikky-Burr, by Quincy Jones, with vocals by Cosby.