Get into an argument with a driver about a cyclist's right to use the road, and at some point expect to hear something like this: "Bikers don't pay for the roads. You don't pay gas taxes. You don't pay license fees. Bikers are leeches on the roads that are built and paid for by car drivers."

If that particular "argument" doesn't sound familiar, then just try to imagine it with a bunch of cuss words and epithets thrown into the mix. Then it might ring a bell.

Well, there was a great article in The Atlantic that appeared this week that takes a look at who the real leeches on the system are, and which any cyclist should really read: The True Costs of Driving.

Did I say any cyclist should read it? Heck - many of us probably already knew or at least suspected as much. Maybe I should say every driver should read it.

Much of the info in that article is based on a study published earlier this year from the Frontier Group and the U.S. PIRG Education Fund. Who Pays for the Roads? It's also well worth checking out.

The basic gist of the Atlantic article, and the U.S. PIRG study, is that gas taxes and other fees directly associated with driving don't even come close to paying the cost of maintaining our existing road infrastructure, much less the cost of new road construction. Those taxes and fees merely give drivers (and even many public policymakers) the false notion that drivers are somehow paying their own way and therefore deserve a privileged position in transportation policy decisions.

Here are some notable excerpts:

"The amount that road users pay through gas taxes now accounts for less than half of what's spent to maintain and expand the road system. The resulting shortfall is made up from other sources of tax revenue at the state and local levels, generated by drivers and non-drivers alike. This subsidizing of car ownership costs the typical household about $1,100 per year -- over and above the costs of gas taxes, tolls, and other user fees."

Understand that that amount is paid by everyone - including those who don't even drive or own cars. The article goes on to show that the amount of that "driver subsidy" has been steadily increasing since the 1950s, and at an accelerated rate in the last 15 - 20 years.

"The huge subsidy to car use has another equally important implication: because user fees are set too low, and because, in essence, people are being paid to drive more, there is excess demand for the road system. If roads were priced to recover even the cost of maintenance, driving would be noticeably more expensive, and people would have much stronger incentives to drive less, and to use other forms of transportation, such as transit and cycling."

That point is particularly relevant in the current climate where even suggesting the possible need for increasing the gas tax is political suicide. An impossibility. The article states, "What the reaction to this hike really signals is that drivers don't value the road system highly enough to pay for the cost of keeping it in operation and maintaining it. Drivers will make use of roads, especially new ones, but only if the cost of construction is subsidized by others."

It is also important to note that because many of the costs associated with driving are hidden in ways that we often don't think about, the true cost of the driving subsidy is actually much higher than the direct dollar amount stated.

Hidden costs? Like what? Well, what about "free" parking? Consider the cost/value of real estate in any city or community, then think about how much of it is given over to the huge parking lots in front of just about any retail center. Such "free parking" isn't really free, but it has become an absolute necessity -- one of the costs of doing business -- and it is paid for by all of us in the form of higher prices for consumer goods, groceries, and more. Many cities still offer free on-street parking as well which should be counted as another "giveaway" and part of the driving subsidy.

There are other costs as well, that are more difficult to quantify in dollar amounts. Congestion. Pollution. Public safety. The shrill and very vocal anti-cycling activists out there, who stand in the way of bicycle infrastructure projects, often throw around bogus "public safety" arguments, saying that cyclists are a threat to safety -- particularly to the very young and the very old. But the fact is that, after a number of years where driving fatalities had been declining, the number of people killed in cars and by cars is now growing. According to recent statistics, the number of people killed in the U.S. in traffic crashes may hit 40,000 this year for the first time since 2007. The number of pedestrians killed by cars in 2013 was more than 4,700 -- many of whom were on sidewalks and in crosswalks. On the other hand, the number of pedestrians killed by bicycles is so small that it's difficult to even find statistics on it. In New York City, according to their Department of Transportation, from 2005 - 2013, the total number was four people (and all 4 probably made major news there). Compared to the rest of the nation, NYC was apparently a bloodbath of bicycle-inflicted carnage.

Next time you find yourself in one of those arguments about a cyclist's right to the road, or when some of your lawmakers start complaining about the cost of "unnecessary" bicycle infrastructure, or they start throwing around bogus arguments about the "proper" use of public funds in transportation projects, be sure to remind people who really pays for the roads. We all do.

Friday, October 30, 2015

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

Bike Safety 101: You And Your Bicycle

This latest installment of the Bike Safety 101 series, produced by Progressive Pictures, shot on a shoestring budget in and around Oakland, California, is a dull and scolding bicycle safety film, You And Your Bicycle.

One thing that makes You And Your Bicycle unusual among bike safety films was that the producers must have been so convinced of its appeal that they actually made the film twice. That's right. You And Your Bicycle was first produced in 1948 (making it one of the earliest films of the genre that I've found), and then re-made almost shot-for-shot with only minor revisions in 1960. Although a couple of sequences simply recycled the exact same footage between 1948 and 1960, the biggest difference between the two versions seems to be the era of the cars that put the hapless riders in peril.

Though no riders ever seem to get seriously injured in the films, the narration seems to highlight -- and even overemphasize -- the potential for death or dismemberment.

In such a manual as the one shown, you'd find such images as these, to completely convince anybody that no sane person would even consider riding a bike:

The first lessons, as always, are on keeping the bike properly maintained.

There's also a section on riding at night, with admonitions against dressing in dark clothing . . .

. . . as well as recommending that riders cover their bikes in a "coat of white enamel" to help them be seen.

There are copies of You And Your Bicycle available on YouTube, as well as on the Prelinger Archive. However, I've found that they often tend to be mis-identified. That is, the 1960 version is often identified as 1948, and vice versa (I'd think the cars would be a pretty clear giveaway which is which). Online copies of the 1960 version that I've seen tend to be pretty poor quality, but there's a pretty decent quality copy of the 1948 edition from YouTube that you can watch right here:

Enjoy!

|

| Opening title shot from the 1960 version of You And Your Bicycle. |

One thing that makes You And Your Bicycle unusual among bike safety films was that the producers must have been so convinced of its appeal that they actually made the film twice. That's right. You And Your Bicycle was first produced in 1948 (making it one of the earliest films of the genre that I've found), and then re-made almost shot-for-shot with only minor revisions in 1960. Although a couple of sequences simply recycled the exact same footage between 1948 and 1960, the biggest difference between the two versions seems to be the era of the cars that put the hapless riders in peril.

Though no riders ever seem to get seriously injured in the films, the narration seems to highlight -- and even overemphasize -- the potential for death or dismemberment.

|

| The 1960 version encourages viewers to pick up a safety manual, like the one shown, from their local police department. |

|

| "Another death that might have been avoided." Yikes! |

Now that we've made sure our bikes are safe, it's time to get some riding lessons.

|

| Here, a police officer explains to kids the relationship of "reaction time" to "stopping distance." |

|

| Don't get "doored" 1948 and 1960. |

|

| "An automobile is not as maneuverable as a bike. So don't swerve in and out of traffic. Follow a straight line and avoid being run down." Holy cow. |

|

| "Don't be a bicycle hitchhiker. An unexpected turn or stop can mean sudden death." |

|

| My favorite part of the whole movie! |

. . . as well as recommending that riders cover their bikes in a "coat of white enamel" to help them be seen.

|

| The filmmaker must have had some financial backing from the makers of Krylon. |

|

| After admonishing kids about riding in the schoolyard, the narrator adds, "Above all, NEVER be a show off. It just doesn't pay." |

There are copies of You And Your Bicycle available on YouTube, as well as on the Prelinger Archive. However, I've found that they often tend to be mis-identified. That is, the 1960 version is often identified as 1948, and vice versa (I'd think the cars would be a pretty clear giveaway which is which). Online copies of the 1960 version that I've seen tend to be pretty poor quality, but there's a pretty decent quality copy of the 1948 edition from YouTube that you can watch right here:

Enjoy!

Monday, October 26, 2015

What's Old is New Again - But Still Dumb

I recently saw this "innovative" new take on the bicycle called the "Bird of Prey" bike. It is described as a "prone" position, and of course its designer, California architect John Aldridge, has lots of claims for how much better it is than either normal bicycles, or typical recumbents.

As opposed to being seated, either on a saddle, or on a recumbent's seat with a backrest, clearly the rider lies face-down, with arms stretched out forward, and legs extended to the rear. As shown in the photos, the rider's abdomen rests on a large, wide pad, while arms are supported by pads on the handlebars. The bike's "Bird of Prey" moniker obviously implies that the position should feel like flying. The makers say that it keeps the rider very aerodynamic, while keeping the center of gravity low, and making for "quick and agile" handling. Supposedly, the position also makes it easy to turn the huge 60-tooth chainring (with an 11-36 cassette on the rear wheel). They also claim that the position makes climbing hills easy, though I have my doubts.

How new is this design? Well, as we often find when looking into the latest bicycle innovations, there's something decidedly familiar here.

Here's an old article dated from 1949:

In addition, I was reminded of several pictures I'd spotted in old issues of Bicycling! magazine.

But such things go back even farther, as shown here:

OK - so it's really nothing new. But what about the advantages over traditional bikes or recumbents?

Well, the aerodynamic advantage could be pretty easily established. Then again, a lot of recumbents also can make that claim. I already mentioned my doubts about climbing hills on such a bike -- which is a common issue with regular recumbents. Without being able to use one's weight to help turn the pedals, climbing hills becomes one of those "I'll get there when I get there" propositions. Get a low gear and just keep spinning.

I also doubt the claimed "agility" with that long wheelbase. I can't picture tight turns on such a bike.

And comfort? Well, a lot of people who have serious comfort issues with regular bikes seem to get some relief on recumbents. But despite the claims by its makers, I don't imagine the Bird of Prey being very comfortable for a ride of any appreciable length, given that one has to basically hold their head up in that unnatural position just to see where they're going. I have no doubt that my neck and shoulders would be aching in no time.

The makers claim that the low center of gravity makes the bike particularly safe, because it would be very difficult (they actually use the word "impossible") to pitch over the bars in a panic stop. Maybe so. But with a rider position so low, I'd really have to wonder about visibility -- either by the rider to see ahead, or by other vehicles to see the rider. I can't help but think that the prospect of riding on roads with much car traffic would be questionable.

No, other than reaching some pretty impressive top speeds, I don't really see this thing catching on today any more than its predecessors did in the '70s, or '49, or even 1917.

As opposed to being seated, either on a saddle, or on a recumbent's seat with a backrest, clearly the rider lies face-down, with arms stretched out forward, and legs extended to the rear. As shown in the photos, the rider's abdomen rests on a large, wide pad, while arms are supported by pads on the handlebars. The bike's "Bird of Prey" moniker obviously implies that the position should feel like flying. The makers say that it keeps the rider very aerodynamic, while keeping the center of gravity low, and making for "quick and agile" handling. Supposedly, the position also makes it easy to turn the huge 60-tooth chainring (with an 11-36 cassette on the rear wheel). They also claim that the position makes climbing hills easy, though I have my doubts.

How new is this design? Well, as we often find when looking into the latest bicycle innovations, there's something decidedly familiar here.

Here's an old article dated from 1949:

|

| This 1949 picture was recently shared with the ClassicRendezvous group by Peter Jourdain. The rider's fashion sense is different (note the high heels!), but the bike looks almost the same. |

|

| This one is probably the same bike as above, but equipped in this case with a plastic fairing to further reduce drag. Also by Dr. Allan Abbott, who set a few speed-records in the '70s. |

|

| I found this one in the Nov. '73 issue of Bicycling! A terrible quality photo, but claimed to be from 1917. It shares a lot with the Bird of Prey bike. |

|

| Then there's this one, the Flying Rider, designed by another California architect, David Schwartz. Like Dr. Abbott's speed-record bikes shown above, the rider dangles underneath by a harness. The main difference here is that the pedals are still below the rider in a relatively "normal" position - but they still make much of the fact that the rider can stretch out prone, simulating the feel of flying like Superman. I still think this looks like some kind of bizarre S&M device. |

OK - so it's really nothing new. But what about the advantages over traditional bikes or recumbents?

Well, the aerodynamic advantage could be pretty easily established. Then again, a lot of recumbents also can make that claim. I already mentioned my doubts about climbing hills on such a bike -- which is a common issue with regular recumbents. Without being able to use one's weight to help turn the pedals, climbing hills becomes one of those "I'll get there when I get there" propositions. Get a low gear and just keep spinning.

I also doubt the claimed "agility" with that long wheelbase. I can't picture tight turns on such a bike.

And comfort? Well, a lot of people who have serious comfort issues with regular bikes seem to get some relief on recumbents. But despite the claims by its makers, I don't imagine the Bird of Prey being very comfortable for a ride of any appreciable length, given that one has to basically hold their head up in that unnatural position just to see where they're going. I have no doubt that my neck and shoulders would be aching in no time.

The makers claim that the low center of gravity makes the bike particularly safe, because it would be very difficult (they actually use the word "impossible") to pitch over the bars in a panic stop. Maybe so. But with a rider position so low, I'd really have to wonder about visibility -- either by the rider to see ahead, or by other vehicles to see the rider. I can't help but think that the prospect of riding on roads with much car traffic would be questionable.

No, other than reaching some pretty impressive top speeds, I don't really see this thing catching on today any more than its predecessors did in the '70s, or '49, or even 1917.

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

There's Light, and There's Stupid-Light

I've said it before, and I'll say it again. There's light. And then there's stupid-light. In case the distinction isn't obvious, stupid-light pushes the boundaries of reliability, safety, and good sense. I just watched a video on BikeRadar about the Top 5 Lightest Road Bikes, and I'm going to have to chalk this stuff up as stupid-light.

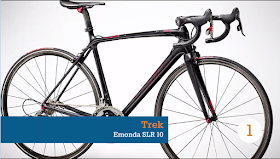

Last year, Trek introduced their Emonda SLR 10, declaring it to be the lightest production bike in the world at just 4.65 kilos, or just over 10 lbs. (10.25, to be exact). The frame is a scant 690 grams, or a pound and a half. Selling for around $15,000, it was and still is out of reach for all but the most dedicated and materialistic weight weenies.

Damn, it's a sick, sick world.

To wit, the video goes on to say, "Though Fuji does not enjoy the 'cool factor' of other brands, it has shown that you don't need boutique components to spec a 5-kilo build for everyday riding and racing."

Next comes the new Canyon Ultimate CF EVO which weighs in at 4.85 kilos or 10.7 pounds.

Knocking the Trek Emonda off the pinnacle of lightest production road bike is the Merida Scultura 9000 LTD. Weighing a claimed 4.5 kilos (9.9 lbs.), the company pushes the limits of carbon fiber construction with frame wall thickness of just 0.4 mm in some sections.

Now, all the bikes on this list earn their stupid-light distinction through liberal uses of carbon fiber - in many cases pared down to the limits of the material. I suppose I should point out that stupid-light bikes can be made in any material, including steel and/or aluminum. Remember drillium? That was stupid-light going old-school. Build a steel frame with 0.3 mm wall thickness (yes, tubing was available that thin) and put it under a big American-sized rider, and you might call that stupid-light, too. But knowing the difference in the way carbon fiber fails (usually quickly, with little warning) vs. the way metals fail (usually cracks will be the first signs of impending failure), I just can't see spending so much money for something so potentially temporary.

Watch the video at the BikeRadar site, or right here:

Enjoy! Meanwhile, I need to go use my Proofide inhaler.

Last year, Trek introduced their Emonda SLR 10, declaring it to be the lightest production bike in the world at just 4.65 kilos, or just over 10 lbs. (10.25, to be exact). The frame is a scant 690 grams, or a pound and a half. Selling for around $15,000, it was and still is out of reach for all but the most dedicated and materialistic weight weenies.

|

| Still crazy a year later. But now it has some competition in the stupid-light stratosphere. |

Damn, it's a sick, sick world.

To wit, the video goes on to say, "Though Fuji does not enjoy the 'cool factor' of other brands, it has shown that you don't need boutique components to spec a 5-kilo build for everyday riding and racing."

|

| Creative math aside, it's still a stupid-light bike. Er, I mean a bike for "everyday riding and racing." For whom??? |

|

| The Fuji's Reynolds RZR wheels feature carbon rims, spokes, and even hubs. No worries about durability with these wheels. Nope. Not at all. And remember - those are for "everyday riding and racing." |

|

| The 665 gram frame is actually lighter than the Trek, so the "extra" weight must come from a 20-gram "porkier" build kit. And you just know that those extra 20 grams equal loads more durability. |

|

| So that's what an "everyday rider" crank looks like. Actually, a couple of the bikes on this Top 5 list use the same THM carbon crank. Notice those huge openings in that spider. No worries. |

Knocking the Trek Emonda off the pinnacle of lightest production road bike is the Merida Scultura 9000 LTD. Weighing a claimed 4.5 kilos (9.9 lbs.), the company pushes the limits of carbon fiber construction with frame wall thickness of just 0.4 mm in some sections.

|

| The Merida's 690-gram frame weight pretty well matches that of the Trek, so the additional weight savings must come from more feathery components. No word on pricing. If you have to ask. . . |

Now, all the bikes on this list earn their stupid-light distinction through liberal uses of carbon fiber - in many cases pared down to the limits of the material. I suppose I should point out that stupid-light bikes can be made in any material, including steel and/or aluminum. Remember drillium? That was stupid-light going old-school. Build a steel frame with 0.3 mm wall thickness (yes, tubing was available that thin) and put it under a big American-sized rider, and you might call that stupid-light, too. But knowing the difference in the way carbon fiber fails (usually quickly, with little warning) vs. the way metals fail (usually cracks will be the first signs of impending failure), I just can't see spending so much money for something so potentially temporary.

Watch the video at the BikeRadar site, or right here:

Enjoy! Meanwhile, I need to go use my Proofide inhaler.

Monday, October 19, 2015

The Latest and Greatest: Plus Size Bikes

It wasn't so very long ago when the term "plus size" referred to people -- usually women -- and most often fashion models with figures and proportions larger than the anorexic waif-like models that so dominate the fashion industry. Almost ironically, many so-called "plus size" models aren't actually so much "plus size" as they are "normal size," so maybe a better term for them would be "life-size."

But I'm digressing.

Because now, the bicycle industry is embracing another new trend -- and yet another narrow marketing segment: "plus size" bicycles.

Not long after fat bikes became so ubiquitous that we can now buy them at Walmart, (and I've even see people using them on pavement!) but some have decided that the 4 - 5-in. tires on fat bikes are a bit too fat for regular use (OF COURSE THEY ARE!). So now the latest trend is to split the difference between the 2.xx-in. of a typical mountain bike, and the 4 - 5-in. of a fat bike. The result is bikes with 3-in. tires, called "mid-fat" by some, or "plus size" by most.

One of the earlier examples has actually been available for a couple years now - the Surly Krampus, which has 3-in. 29er tires on wide 50mm rims. More of the bigger companies are now releasing plus-size bikes and tires built around wider 27.5 wheels (called 27+ which should not be confused with the old 27-in. wheels common to many older "ten-speed" bikes), and around 29er wheels (called 29+).

Of course, one can't just shove wider tires into any old frame, so if someone wants to experience the latest thing in mountain bikes, it most likely means buying yet another new bike. I've read that some of the 27+ tires/wheels might fit into some existing 29er frames, but don't count on it.

The other issue is that of incompatible standards (there's that troublesome - and meaningless - word again). Putting such wide tires into a frame often necessitates some frame-geometry gymnastics. Longer wheelbase. Wider-spaced chainstays. Wider hub spacing. Any/all of the above. So for rear wheel spacing, we now have the "old" standard of 135mm, or newer 142mm (for thru-axles), or the still newer "Boost 148" standard, which is wider not only across the axle end caps, but also across the hub flanges.

The latest thing in mountain bikes is getting hyped pretty breathlessly. You know the story. You haven't experienced anything like it. You have to experience it for yourself. It will transform your rides. More specific claims are that the massive tires give more grip and stability, like their fat-bike counterparts, but without the extra weight and truck-like handling (seems kind of obvious). Trek says on their site "The wide 3-in. tires grip relentlessly, amplifying all the benefits of 29ers . . . You'll be amazed at how the capable, unshakable 29+ tires immediately allow you to corner harder and faster without breaking loose." We'll all just have to rush out to buy another bike.

With yet another narrow segment introduced to the bicycle marketplace (and a couple new "standards" to boot), it makes a person wonder whether the industry comes up with things like this out of a desire to innovate, or a sense of desperation.

But I'm digressing.

Because now, the bicycle industry is embracing another new trend -- and yet another narrow marketing segment: "plus size" bicycles.

|

| The Surly Krampus is what some might call a 29+ with its 3-in. tires on 50-mm wide 29er rims. (photo from Surlybikes) |

One of the earlier examples has actually been available for a couple years now - the Surly Krampus, which has 3-in. 29er tires on wide 50mm rims. More of the bigger companies are now releasing plus-size bikes and tires built around wider 27.5 wheels (called 27+ which should not be confused with the old 27-in. wheels common to many older "ten-speed" bikes), and around 29er wheels (called 29+).

Of course, one can't just shove wider tires into any old frame, so if someone wants to experience the latest thing in mountain bikes, it most likely means buying yet another new bike. I've read that some of the 27+ tires/wheels might fit into some existing 29er frames, but don't count on it.

|

| The new Trek Stache 29+ manages to fit plus-size tires with short stays and an extra-wide rear triangle. (photo from Trekbikes) |

The other issue is that of incompatible standards (there's that troublesome - and meaningless - word again). Putting such wide tires into a frame often necessitates some frame-geometry gymnastics. Longer wheelbase. Wider-spaced chainstays. Wider hub spacing. Any/all of the above. So for rear wheel spacing, we now have the "old" standard of 135mm, or newer 142mm (for thru-axles), or the still newer "Boost 148" standard, which is wider not only across the axle end caps, but also across the hub flanges.

The latest thing in mountain bikes is getting hyped pretty breathlessly. You know the story. You haven't experienced anything like it. You have to experience it for yourself. It will transform your rides. More specific claims are that the massive tires give more grip and stability, like their fat-bike counterparts, but without the extra weight and truck-like handling (seems kind of obvious). Trek says on their site "The wide 3-in. tires grip relentlessly, amplifying all the benefits of 29ers . . . You'll be amazed at how the capable, unshakable 29+ tires immediately allow you to corner harder and faster without breaking loose." We'll all just have to rush out to buy another bike.

With yet another narrow segment introduced to the bicycle marketplace (and a couple new "standards" to boot), it makes a person wonder whether the industry comes up with things like this out of a desire to innovate, or a sense of desperation.

Wednesday, October 14, 2015

Original Paint - Galmozzi Update

Last summer, I had a story about an interesting 1960s Galmozzi belonging to an acquaintance, Kevin Kruger. At some point in the bike's long history it had been repainted and re-decalled as something other than what it really was. In preparing the bike for a proper restoration, Kevin discovered that the bike's original paint was still largely intact underneath the repaint. After carefully scraping and stripping that overpaint, and with some careful touch-ups, he ended up with a frame that is very nice, original, and has a patina that suggests a great history -- and a fantastic story.

When that post ended, the bike was ready for some reproduction decals and waiting for a period-appropriate set of components. Well, last I checked, the bike was completed, and today seemed like a good day to post an update on that original paint Galmozzi.

According to Kevin, the restoration decals came from Greg Softley at Cyclomondo. The bike was built up with early '60s Campagnolo Record components (that's Record -- not Nuovo Record), except for the brakes which are Universal 61 centerpulls. Remember that Campy didn't yet have a brakeset on the market when this bike would have been built originally. The wheels have classic Fiamme red label tubular rims and large flange Campagnolo hubs dated "63" - and made before Campy started engraving the "Record" name on them (usually called "No Record" hubs by collectors). Stem and bars are 3ttt Gran Prix, which seem like a good choice for the time, and the saddle is a drilled-top Cinelli Unicanitor.

Hats off to Kevin for a great job on this preservation/restoration. The bike looks great and would be a proud addition to any vintage collection. A full set of photos can be seen on Kevin Kruger's Flickr page.

And a Totally Unrelated Update:

In August, I wrote about bike commuting and weight loss. In that article, I talked about my theory of how two shorter rides in a day might be more advantageous than one longer ride if one were trying to lose weight. That was based on my own experience that when I started commuting to and from work by bicycle, I found myself losing a fair amount of weight, practically without trying to. At the time I was writing that, at the end of my summer break, I was looking forward to getting back to my regular bike commuting, and hoping to lose a few extra pounds.

Now that we're nearing the middle of October, I can report that my bike-to-work average is holding steady at about 75% (in other words, I'm riding to work 3 out of every 4 days). In all practicality, it would be really hard to improve that average much, since there are times that I simply have to drive, regardless of weather -- sometimes I just need to get somewhere quickly after work, and biking is simply unfeasible. In fact, I'm on track so far break any of my previous personal records. Understand that it's still early (and I'm probably jinxing things), and if we have another winter as bad as the last two, it could easily wipe out any advantage I may build up. A couple of years ago, I had nearly as good of a an average in the fall, but a terrible winter killed it. But so far, this fall has been just about perfect for biking. By the way, my goal for the year (winter included) is to keep an average of 50%. I've only managed that feat once since I started bike commuting more than three years ago.

In addition, I've dropped about 7 or 8 pounds since the end of August. I'm right at 150 lbs. today, which is where I was hoping to be. Now, if I could just get better about cutting back on carbs, I might finally be able to get back to 145 lbs, which is what I weighed when I finished college so many years ago. Too bad I love bread and pasta so much.

Hope the fall weather is treating all of you as kindly as it is here in Ohio.

|

| After. All the blue paint has been removed, and some chips and scratches have been touched up. When we last saw it, the bike was ready for some new decals and components. |

When that post ended, the bike was ready for some reproduction decals and waiting for a period-appropriate set of components. Well, last I checked, the bike was completed, and today seemed like a good day to post an update on that original paint Galmozzi.

|

| Complete and ready to ride. |

|

| I've always liked that rooster head badge. |

And a Totally Unrelated Update:

In August, I wrote about bike commuting and weight loss. In that article, I talked about my theory of how two shorter rides in a day might be more advantageous than one longer ride if one were trying to lose weight. That was based on my own experience that when I started commuting to and from work by bicycle, I found myself losing a fair amount of weight, practically without trying to. At the time I was writing that, at the end of my summer break, I was looking forward to getting back to my regular bike commuting, and hoping to lose a few extra pounds.

Now that we're nearing the middle of October, I can report that my bike-to-work average is holding steady at about 75% (in other words, I'm riding to work 3 out of every 4 days). In all practicality, it would be really hard to improve that average much, since there are times that I simply have to drive, regardless of weather -- sometimes I just need to get somewhere quickly after work, and biking is simply unfeasible. In fact, I'm on track so far break any of my previous personal records. Understand that it's still early (and I'm probably jinxing things), and if we have another winter as bad as the last two, it could easily wipe out any advantage I may build up. A couple of years ago, I had nearly as good of a an average in the fall, but a terrible winter killed it. But so far, this fall has been just about perfect for biking. By the way, my goal for the year (winter included) is to keep an average of 50%. I've only managed that feat once since I started bike commuting more than three years ago.

In addition, I've dropped about 7 or 8 pounds since the end of August. I'm right at 150 lbs. today, which is where I was hoping to be. Now, if I could just get better about cutting back on carbs, I might finally be able to get back to 145 lbs, which is what I weighed when I finished college so many years ago. Too bad I love bread and pasta so much.

Hope the fall weather is treating all of you as kindly as it is here in Ohio.

Monday, October 12, 2015

Torch and Lumos LED Helmets

I was just reading about a couple of new helmets with integrated LED lighting that are hitting the market. One is the Torch T2, which was out on Kickstarter a couple of years ago, and is now available for sale through the company's website. More recent is the Lumos, which met its Kickstarter goal in just one day this past summer (and exceeded it many times over before it was through), and I assume it should be ready for sale soon.

I have a feeling that a lot of readers would expect me to skewer products like these pretty mercilessly, but as a bicycle commuter who rides quite a bit in the pre-dawn darkness, I have to say that I'm at least curious about the things. It seems to me that having a little extra lighting to add to a rider's night-time visibility can't hurt - and if it can be done seamlessly without strapping on more bits and pieces, so much the better.

Between the two, I think I'd be more inclined to try out the Lumos, which looks more like a typical modern road helmet. The light system seems to be pretty well integrated into the design. The Torch T2 has that skater-helmet style, and appears to be a bit bulky, and only has a few small, narrow vents. Of course, it's a matter of preference and taste, but I've never been a big fan of that type of helmet design. In colder weather, the skater-style helmet might be okay, but in most weather, I find that my head generally wants a lighter, more ventilated helmet.

The new Lumos helmet claims to take the light-up helmet idea a little further than the Torch. One of the key features is not just that it has LED lights both front and rear, but that the lights are supposed to function as brake lights and turn signals. Truly necessary? Probably not. But assuming they actually work as claimed, they wouldn't be a deal breaker.

Reading more about the helmet on the Lumos site, the helmet's rechargeable battery is built in, and can be recharged with a typical micro-USB cable. One minor worry I'd have is water resistance. The website claims "You shouldn't dunk Lumos into a pool, but Lumos is water resistant so you can take it out with you rain or shine." How resistant is that, should one get caught in a major downpour (where visibility is almost as important as at night), I'd like to know. Also, I'm someone who often rinses out my helmet after a sweaty ride, to clean up the straps and internal pads -- and that doesn't exactly involve dunking my helmet into a pool, but it probably isn't far off. Hmmm. . .

Some thoughts:

While having some extra lighting to add to a rider's visibility is probably a good idea, I don't think people should get the idea that either of these light-up helmets is a substitute for a set of good quality bike-mounted lights (and from what I've read, neither company claims that they are such a substitute).

As far as the turn-signal and brake-light functions of the Lumos, I don't know if those are really necessary. If those features work as they're supposed to, they might be fine -- but if they don't, they'd be a serious annoyance. Also, they add to the cost, and could become just another thing to go on the fritz. On the whole, I'd probably be just as happy ditching the added complexity and simply having static non-flashing lights for visibility.

This morning on my ride to work, in that early morning darkness, I did find myself contemplating my visibility to the drivers on the road. I've looked into some of the helmet-mount lights that are available, and have even tried a couple, but I've never been really happy with the fit or the look of those lights. So, while these light-up helmets might not be for everyone, it seems that - at least for regular commuters - they might be some technology worth looking into.

|

| The Torch has that skater-helmet look to it. It also appears to be a bit bulky. |

Between the two, I think I'd be more inclined to try out the Lumos, which looks more like a typical modern road helmet. The light system seems to be pretty well integrated into the design. The Torch T2 has that skater-helmet style, and appears to be a bit bulky, and only has a few small, narrow vents. Of course, it's a matter of preference and taste, but I've never been a big fan of that type of helmet design. In colder weather, the skater-style helmet might be okay, but in most weather, I find that my head generally wants a lighter, more ventilated helmet.

The new Lumos helmet claims to take the light-up helmet idea a little further than the Torch. One of the key features is not just that it has LED lights both front and rear, but that the lights are supposed to function as brake lights and turn signals. Truly necessary? Probably not. But assuming they actually work as claimed, they wouldn't be a deal breaker.

|

| A pair of wireless remote buttons mounted on the handlebar controls the helmet's turn signals. |

Reading more about the helmet on the Lumos site, the helmet's rechargeable battery is built in, and can be recharged with a typical micro-USB cable. One minor worry I'd have is water resistance. The website claims "You shouldn't dunk Lumos into a pool, but Lumos is water resistant so you can take it out with you rain or shine." How resistant is that, should one get caught in a major downpour (where visibility is almost as important as at night), I'd like to know. Also, I'm someone who often rinses out my helmet after a sweaty ride, to clean up the straps and internal pads -- and that doesn't exactly involve dunking my helmet into a pool, but it probably isn't far off. Hmmm. . .

Some thoughts:

While having some extra lighting to add to a rider's visibility is probably a good idea, I don't think people should get the idea that either of these light-up helmets is a substitute for a set of good quality bike-mounted lights (and from what I've read, neither company claims that they are such a substitute).

As far as the turn-signal and brake-light functions of the Lumos, I don't know if those are really necessary. If those features work as they're supposed to, they might be fine -- but if they don't, they'd be a serious annoyance. Also, they add to the cost, and could become just another thing to go on the fritz. On the whole, I'd probably be just as happy ditching the added complexity and simply having static non-flashing lights for visibility.

This morning on my ride to work, in that early morning darkness, I did find myself contemplating my visibility to the drivers on the road. I've looked into some of the helmet-mount lights that are available, and have even tried a couple, but I've never been really happy with the fit or the look of those lights. So, while these light-up helmets might not be for everyone, it seems that - at least for regular commuters - they might be some technology worth looking into.

Friday, October 9, 2015

An Argument Against Anti-Cycling Propaganda

Browsing through some other bike blog articles, I just happened on this article from the the U.K.-based Velomanifesto Blog:

It was originally posted back in April (though it's still perfectly relevant), and deals specifically with the politics of bicycle infrastructure in Britain, but some of the issues brought up would be very familiar to cyclists no matter where they may live.

As a little background and explanation for readers outside the U.K., the article was spurred by a political flier distributed by the UK Independence Party (UKIP) that scapegoats cyclists and attacks the use of public funding for bicycle infrastructure projects.

Not being totally familiar with the political landscape in the U.K., I had to do a little reading on UKIP to find that they call themselves a "libertarian" party, but are characterized by many political scientists as a right-wing Eurosceptic party that aims to pull the nation out of the European Union.

Many of the arguments made in the flier are the same kind of illogical cyclist-baiting drivel I'm sure we all hear all too often, in any country. Some examples:

"Cyclists are the chosen people, motorists are simply a cash cow and have very few rights."

"Surely giving all the rights to cyclists, who are usually young people, is discriminating against the elderly and infirm."

"Try walking across the Town Moor when a cyclist is silently whizzing along at 20 mph, one move to the left or right could cause serious injuries to a pedestrian."

"Cyclists carry no number plate or insurance."

"If the council is so concerned about public safety why don't they get cyclists to put bells on their bikes?"

We've all heard similar arguments -- that spending public money on anything other than automobile-specific infrastructure is a waste of money, or gives "special rights" to cyclists. That cyclists don't pay taxes, and therefore shouldn't be allowed on the roads. That cyclists somehow pose a bigger threat to pedestrians -- especially the very old and very young -- than cars. That putting more mandates on cyclists and their bikes will somehow make the public safer. The list goes on and on.

What particularly made the Velomanifesto article worth reading was the way he rebuts and refutes each one of those arguments.

Here's a sample - a response to the "Cyclists are the chosen people" argument:

"Cyclists are the chosen people? We certainly are. A commute by bicycle on any given day demonstrates this fact. The way motorists cut us up and drive too close . . . the verbal abuse we receive on a daily basis from motorists, the constant danger of dogs not on leads, glass on the side of the road, trip wires put across cycle paths with dog s%*t in bags hanging off them, the constant fear of being "doored," the fact that pedestrians step out without looking, the risk of cars overtaking through traffic islands . . . yes. . . we are indeed the deity of the road. At times it feels as if the roads were put there just for us."

As for the argument we all have heard about cyclists not paying road taxes (or gas taxes, or any taxes at all according to some), he calls it the "usual ill-informed line that motorists bring up on an anti-cyclist rant." He goes on to point out that the majority of adult cyclists DO own cars, and pay all the usual fees and taxes associated with them. But also, that roads are not funded solely through road taxes or gas taxes -- but are paid for by all the various kinds of taxes everyone pays (here in the U.S., that includes federal, state, and local income taxes, local property taxes, and even sales taxes) whether they own a car or not. He concludes on that point, "We're ALL paying for the roads and therefore have an equal right to use them."

Although the article was specifically about a U.K.-based issue, it's worth a read for anyone who's found themselves in the midst of an anti-cyclist argument.

It was originally posted back in April (though it's still perfectly relevant), and deals specifically with the politics of bicycle infrastructure in Britain, but some of the issues brought up would be very familiar to cyclists no matter where they may live.

As a little background and explanation for readers outside the U.K., the article was spurred by a political flier distributed by the UK Independence Party (UKIP) that scapegoats cyclists and attacks the use of public funding for bicycle infrastructure projects.

Not being totally familiar with the political landscape in the U.K., I had to do a little reading on UKIP to find that they call themselves a "libertarian" party, but are characterized by many political scientists as a right-wing Eurosceptic party that aims to pull the nation out of the European Union.

Many of the arguments made in the flier are the same kind of illogical cyclist-baiting drivel I'm sure we all hear all too often, in any country. Some examples:

"Cyclists are the chosen people, motorists are simply a cash cow and have very few rights."

"Surely giving all the rights to cyclists, who are usually young people, is discriminating against the elderly and infirm."

"Try walking across the Town Moor when a cyclist is silently whizzing along at 20 mph, one move to the left or right could cause serious injuries to a pedestrian."

"Cyclists carry no number plate or insurance."

"If the council is so concerned about public safety why don't they get cyclists to put bells on their bikes?"

We've all heard similar arguments -- that spending public money on anything other than automobile-specific infrastructure is a waste of money, or gives "special rights" to cyclists. That cyclists don't pay taxes, and therefore shouldn't be allowed on the roads. That cyclists somehow pose a bigger threat to pedestrians -- especially the very old and very young -- than cars. That putting more mandates on cyclists and their bikes will somehow make the public safer. The list goes on and on.

What particularly made the Velomanifesto article worth reading was the way he rebuts and refutes each one of those arguments.

Here's a sample - a response to the "Cyclists are the chosen people" argument:

"Cyclists are the chosen people? We certainly are. A commute by bicycle on any given day demonstrates this fact. The way motorists cut us up and drive too close . . . the verbal abuse we receive on a daily basis from motorists, the constant danger of dogs not on leads, glass on the side of the road, trip wires put across cycle paths with dog s%*t in bags hanging off them, the constant fear of being "doored," the fact that pedestrians step out without looking, the risk of cars overtaking through traffic islands . . . yes. . . we are indeed the deity of the road. At times it feels as if the roads were put there just for us."

As for the argument we all have heard about cyclists not paying road taxes (or gas taxes, or any taxes at all according to some), he calls it the "usual ill-informed line that motorists bring up on an anti-cyclist rant." He goes on to point out that the majority of adult cyclists DO own cars, and pay all the usual fees and taxes associated with them. But also, that roads are not funded solely through road taxes or gas taxes -- but are paid for by all the various kinds of taxes everyone pays (here in the U.S., that includes federal, state, and local income taxes, local property taxes, and even sales taxes) whether they own a car or not. He concludes on that point, "We're ALL paying for the roads and therefore have an equal right to use them."

Although the article was specifically about a U.K.-based issue, it's worth a read for anyone who's found themselves in the midst of an anti-cyclist argument.

Wednesday, October 7, 2015

There's an App for That: Derailleur Adjustment

After looking recently at Bluetooth pumps that use a smartphone app for a pressure gauge, I found that there really does seem to be an app for everything now -- even derailleur adjustment.

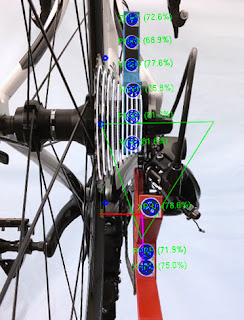

That's right. The OTTO Tuning System (which sounds almost like "auto-tuning," doesn't it?) uses yet another smartphone app, along with a pair of cassette and derailleur position gauges, to make drivetrain adjustment as mindless as everything else now controlled by smartphone. For people who feel that virtually no task should be undertaken without the assistance of their phone, this must be welcome news.

According to the product introduction video, the system "doesn't require any prior bicycle service experience," and one should be able to achieve "perfect shifting in under 5 minutes." The company touts the precision of the system as being accurate to within +/- 0.125 mm. Holy cow.

They also claim that it can "diagnose bent dropout hangers, worn cables, and poorly adjusted limit screws." I suppose it makes sense that the system can diagnose dropout hangers and limit screws, since both of those things would be picked up by checking the alignment of the gauges. How on earth it can detect worn cables is beyond me. Then again, why would anyone possibly need an app to tell them their cables are worn? Are they frayed? Kinked? Rusty? Those should be clear just from looking.

I wonder if the app can diagnose THIS:

So far, the app is only made for the Apple iOS operating system, but supposedly an Android version is in the works.

I will say that, at $39, (that's for the gauges - the app is apparently free, but useless without the gauges) the OTTO Tuning System is at least a relatively inexpensive tool. The company says the system is Shimano and SRAM 9-10-11 speed compatible -- but not Campagnolo. I find that partially odd, since I was under the impression that the cog spacing of 11-speed drivetrain systems was the same for all three companies (at least that's what Lennard Zinn says). I guess it doesn't matter, though, since none of my bikes goes to 11. In fact, most of my bikes still use friction shifting. It probably goes without saying, but the OTTO Tuning System is also incompatible with friction -- and mostly unnecessary in any case.

There are demonstration videos on the OTTO website, or you can see their product introduction video right here:

Useful tool? Or another example of smartphone addiction? I wouldn't mind hearing some thoughts.

|

| Clip these little gauges onto the cassette and derailleur then use the smartphone to fine-tune adjustment. (photo from OTTO) |

According to the product introduction video, the system "doesn't require any prior bicycle service experience," and one should be able to achieve "perfect shifting in under 5 minutes." The company touts the precision of the system as being accurate to within +/- 0.125 mm. Holy cow.

They also claim that it can "diagnose bent dropout hangers, worn cables, and poorly adjusted limit screws." I suppose it makes sense that the system can diagnose dropout hangers and limit screws, since both of those things would be picked up by checking the alignment of the gauges. How on earth it can detect worn cables is beyond me. Then again, why would anyone possibly need an app to tell them their cables are worn? Are they frayed? Kinked? Rusty? Those should be clear just from looking.

I wonder if the app can diagnose THIS:

|

| The OTTO website calls this phone screenshot "augmented reality." I'll say it's "augmented." somehow they got the drivetrain on the left side of the bike! |

|

| Apparently the phone's camera "reads" the dots on the alignment gauges, then uses some algorithms to determine what adjustments are necessary. Listen to the slightly robotic-sounding woman's voice explain, "Turn your barrel adjuster 4 clicks clockwise." (photo from OTTO) |

I will say that, at $39, (that's for the gauges - the app is apparently free, but useless without the gauges) the OTTO Tuning System is at least a relatively inexpensive tool. The company says the system is Shimano and SRAM 9-10-11 speed compatible -- but not Campagnolo. I find that partially odd, since I was under the impression that the cog spacing of 11-speed drivetrain systems was the same for all three companies (at least that's what Lennard Zinn says). I guess it doesn't matter, though, since none of my bikes goes to 11. In fact, most of my bikes still use friction shifting. It probably goes without saying, but the OTTO Tuning System is also incompatible with friction -- and mostly unnecessary in any case.

There are demonstration videos on the OTTO website, or you can see their product introduction video right here:

Useful tool? Or another example of smartphone addiction? I wouldn't mind hearing some thoughts.