Anyhow. . .

With the 2016 Olympics having just wrapped up, I found this article the other day on the CyclingTips website about the Project '96 Superbike, built for the '96 Olympic Games in Atlanta.

Some readers may remember the GT Superbikes, though it was 20 years ago so there's no guarantee. Twenty years ago?! Wow. It's hard to believe.

The Superbike II, as it was known, was the culmination of a major engineering effort between USA Cycling, GT Bicycles, and Mavic components, with input from people such as aerodynamics expert Chester Kyle, and the aerodynamics lab at General Motors. The bike was recognizable for its unusual top-tube-less carbon fiber monocoque frame, airfoil shapes, and extremely narrow aerodynamic profile. When viewed from the front, the bike was barely any wider than its disc wheels. The bike also had no seat stays, and the seat mast was shaped to act as a large fairing for the rear wheel.

By the way - Superbike II? Well, there was a GT Superbike I, which was made of aerodynamic profiled aluminum tubing, and has been described as sort of a "stopgap" on the way to the design freedom that carbon fiber would give the designers for the "ultimate" racing bike, Superbike II.

The CyclingTips article reveals quite a bit about Project '96 Superbike, hailing it as a revolution -- perhaps even the apex of the no-holds-barred aerodynamic school of bicycle design. I also detect a note of "just think of where we'd be today" lamentation in the story -- if only the UCI weren't so backwards. "The bike was fast. Perhaps too fast," the article says. It goes on:

"Unfortunately for GT and other similarly innovation-minded companies, though, the UCI set out to squelch those technological advantages shortly after the Superbike II broke ground in Atlanta . . . Superbike just pushed it too far."

Just think where racing bikes would be today - if only. . .

|

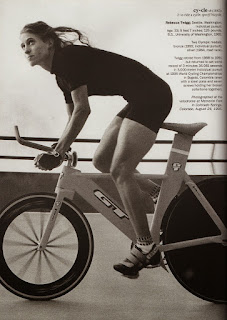

| Rebecca Twigg, aboard Superbike I. Twigg was probably the best hope for US Cycling in the '96 Olympics, but it was not to be. Regarding Superbike II, Twigg was not a fan. |

Regarding fit, it's pretty apparent just from looking at the bike that dialing in the perfect fit for an individual racer wasn't exactly an easy thing to do. The integrated seat mast meant that making any adjustments to saddle height or angle was a complicated and slow process.

And even if one accepts the notion that the carbon fiber monocoque design was a great thing, I'm not sure I can accept that the Superbike was all that unique for the time. It certainly wasn't the "secret weapon" that some hypesters would have us believe.

For example - look at the Lotus 108. Originally designed in the mid 1980s, the bike was shelved when the UCI ruled such designs illegal for competition in 1987. In 1990, the ban on monocoque designs was lifted, and the 108 was used for a number of international races, including the '92 Olympics in Barcelona, ridden to gold under Chris Boardman.

|

| Lotus 108 |

|

| Indurain setting a new Hour Record in '94 on the Espada. |

|

| The same basic design as a road time trial bike helped take him to his 5th Tour de France victory. |

With what amounted to an "arms race" in designers trying to buy their way to more victories and gold medals, the UCI did change the rules again in 2000 to put limits on these increasingly outlandish bike designs, and with that, bikes like the Superbike II were done. The CyclingTips article seems to imply that the Superbike was the reason for the rules change, or at least the "straw that broke the camel's back," but as we can see, there were plenty of other bikes at the time that followed a similar plan, and if one looks mainly at race results as the measure, then the others had more to show.

Simply put, this article on The Cycling Tips site was written towards newcomers who don't know a thing about existence of at least Boradman's Lotus. Hence the praise in the comment section.

ReplyDeleteGreat posting. I saw a Superbike II hanging from the ceiling at Cycle Smithy Chicago only months ago... expensive decor.

ReplyDeleteWagner

The expression on Rebecca Twigg's face can almost be read as an expression of her discomfort with the bike.

ReplyDeleteI find it amusing when the UCI bans bikes or equipment for being "too light". This is the same UCI that, for decades, looked the other way when doping was rampant.

As the guys from "The GCN Show" (an excellent YouTube cycling channel) pointed out: "if it weren't for the UCI's rules, everybody would be racing on recumbents"

ReplyDelete